Meet 2017 Miracle Kid Savannah Rodriguez

“Though she be but little, she is fierce!” The often-used quote from William Shakespeare has never been more put into practice than by 3-year-old Savannah Rodriguez of Mill Hall.

Savannah was born early on Jan. 2, 2014, at almost 27 weeks resulting in a 7-week stay in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at Geisinger Janet Weis Children’s Hospital.

“She had a pretty run-of-the-mill NICU course,” said Lauren Johnson Robbins, MD, neonatologist at Geisinger Janet Weis Children’s Hospital. “She had some oxygen issues that we see with children born at 27 weeks and a small issue with her heart, which resolved itself, but she was home by Feb. 22 after a relatively short course.”

Her parents, Sabrina and Manuel, also felt relatively at ease during her stay in the NICU.

“When we were still in the hospital, the things she had going on, I was comfortable with them because they were things that happen to every premature baby. I knew the doctors had it under control,” Manuel said.

Savannah came home with a apnea monitor and the need for occasional caffeine drops to assist her in breathing, but after a month of being home, she was weaned off of the machine and the medication.

On March 24 and 25, when Savannah weighed only five pounds, something went terribly wrong.

“During the night she woke up crying — it was an inconsolable type of crying. We couldn’t figure out what was wrong,” Sabrina said. “I spent the night in the rocking chair with her. She would calm down a little, but would start right back up again.”

Savannah always wanted her bottle, but she would not feed. In the morning, Sabrina called the pediatrician. The doctor was very busy and said they could see Savannah later in the afternoon. But 15 minutes later Savannah turned gray ‑‑ something was going terribly wrong.

“I called the doctor back and said, ‘If you can’t see us right now, we are going to Danville.’ They told us to come in and she would see her immediately between patients,” Sabrina said. “We went in and the doctor listened to her belly and said, ‘Something is wrong. I don’t hear any bowel sounds.’”

The doctor told the Rodriguezes that they needed to take Savannah to the nearby community hospital immediately. Sabrina was worried because Savannah had been a premature infant. She told the doctor she would take her to Geisinger Janet Weis Children’s Hospital.

“That is when I got the first idea of how serious this was. The doctor looked at me and said, ‘She won’t make it to Danville,’” Sabrina recalled.

The doctor grabbed Savannah and jumped in the Rodriguezes’ car and rode with them to the hospital. The doctor escorted them into the emergency room and told the staff that Savannah needed triage immediately. An X-ray determined that there was a blockage in Savannah’s small bowel.

Because of the baby’s size and her dire need for specialized care, the hospital staff made immediate plans to transport Savannnah to Geisinger Janet Weis Children’s Hospital.

“When we got to Geisinger, they quickly confirmed the blockage and said they would have to do exploratory surgery,” Sabrina said.

Christopher Coppola, MD, pediatric surgeon was called upon for the procedure.

“When she arrived, she looked extremely ill, so we did some quick testing and got her into the operating room,” Dr. Coppola said. “If it would have been a matter of hours more, she wouldn’t have survived.”

Dr. Coppola discovered that Savannah was suffering from malrotation, where the intestines twist, cutting off blood supply. The condition is one where every minute counts.

“Until the intestine is untwisted, it is dying from that point because of the lack of blood flow,” he said.

As a baby develops, the three divisions of the gastrointestinal tract — the foregut, midgut, hindgut — herniate out from the abdominal cavity, where they then undergo a 270 degree counterclockwise rotation. Malrotation, also known as intestinal nonrotation or incomplete rotation, refers to any variation in this rotation and fixation of the GI tract during development.

“Everyone starts out as a malrotation, which means your gut is on the wrong side,” Dr. Johnson explained. “In development or in utero, it flips to the right side and it kind of gets tacked down so it can’t twist. When you are in malrotation, it never settles itself down and the risk is it floats free. Being malrotated isn’t the problem, it is the fact that it can have volvulus, or a twist in on itself.”

Malrotation can happen at any time and people can go for years not knowing they have the condition.

“I have treated newborns with the condition and I have treated 70-year-old patients,” Dr. Coppola said. “It is almost like a timebomb. No one knows why it happens. It could happen from physical or athletic activity. It can happen from gas and digestion. Once it happens, the twisting pinches the blood vessel shut, the same way if you twisted shut the mouth of a bread loaf bag.”

With no blood supply, the intestines become gangrenous and begin to necrotize, which leads to the loss of gut. Dr. Coppola explained the diagnosis to Sabrina and Manuel.

“Dr. Coppola came out of the operating room and said, ‘It is usually at this point, with what I see inside of her, that I come to parents and tell them there is nothing more that I can do,’” Sabrina remembered, as tears welled up in her eyes. “But he said, ‘I still see some signs of hope.’ He told us that he had to leave her intestines out of her belly in a bag called a silo, to see what would come back after blood flow returned to the intestines.”

Savannah spent the night in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

“We called everyone we knew and told them to come over, because no one really expected her to make it through the night,” Sabrina said.

“As a father, I think dads develop this mentality of ‘It’s broken ‑‑ I have to fix it,’” Manuel said. “It was so difficult when I saw her in that room. I was a firefighter for years in Long Island and I did everything I could to help people all the time. There I stood and I couldn’t do anything for my daughter at all to help her. I felt so helpless.”

Savannah did amazingly well through the night. Her heart and breathing remained strong. The next day, Dr. Coppola said he would take her into the operating room to see how much of her intestines could be saved.

She went through another two-hour surgery. Dr. Coppola was only able to save about 19 inches (50 centimeters) of Savannah’s bowel. Most babies have three to four feet of intestines. Savannah also lost her ileocecal valve, which is a sphincter muscle valve that separates the small intestine and the large intestine. The valve serves as a brake between the small intestine and the colon and helps the body to absorb more nutrients.

The shorter length of her intestines and lack of an ileocecal valve led to Savannah having short bowel syndrome, an absorption disorder, requiring her to be fed intravenously until she was 2 years old by total parenteral nutrition (TPN). TPN is a method of feeding that bypasses the gastrointestinal tract, by giving fluids into a vein to provide most of the nutrients the body needs.

“A person can live with just TPN, because you are providing all the fat and proteins and nutrients and giving the body everything it needs to grow,” said Dean Focht, MD, director of pediatric gastroenterology at Geisinger Janet Weis Children’s Hospital. “The problem is how it is broken down by the liver. Some kids can do well with TPN for an extended period of time, but there are other kids whose liver will develop inflammation. If you don’t get them off quickly enough, the inflammation can go on to develop scar tissue and significant liver problems.”

After the surgery, Savannah was going to need to stay at the hospital for a prolonged time because of her size, her age and the disease process. Her caregivers decided that she would be better cared for in the NICU for her recovery.

“We were very fortunate to have Dr. Johnson and the NICU staff back on her case,” Sabrina said. “She was in the hospital for two more months. We did not leave until June 14.”

“She came down to the NICU for her long-term management,” Dr. Johnson said. “She was still a very sick little girl, and she had to be put back on the ventilator for a period of time during recovery.”

Savannah did surprisingly well. Initially, her providers expected that she would need to be in the hospital for five months and that she would have to go home with a colostomy bag. However, before she was released, Dr. Coppola was able to reconnect her colon. This eliminated some worries for the Rodriguezes who had to learn how to care for their child at home.

The hardest thing was administering the TPN.

“Every time we had to do it, we would have to get the dog out of the room. We had to make sure everything was wiped down. Make sure we scrubbed our hands,” Manuel said. “We stocked up on lotion because we had to wash our hands so much.

“It was real scary when we had to do it ourselves, especially a couple of times when we had to do our own dressing change with the TPN, which was so much worse cause it was so much more sterile.”

On top of the stress of administering the treatment, TPN was very hard on Savannah’s liver.

“It is kind of like a double-edged sword. TPN gave her all the nutrition she needed and was helping her grow, but at the same time it was destroying her liver slowly,” Manuel said. “You should not have all those vitamins and things going directly in your blood, it should be absorbed through the intestines. Her liver was taking the impact head on.”

Beyond the risks to the liver when administering TPN, there is always a chance of infection with bacteria or anything that is in the environment, according to Dr. Focht.

“If you get an infection with a central line, you end up in the hospital. Any fevers, and the patient is immediately brought to the ER. You can’t say, ‘This might be a cold.’ You have to watch them very closely,” he said.

Savannah’s central line was subject to multiple infections, and she needed to have new lines placed several times.

“She had about four different lines because of infections and a blood clot. It was a nightmare,” Sabrina said.

Sabrina and Manuel worked hard to introduce foods to Savannah and figure out what she could tolerate and digest. It was a lot of trial and error, figuring out what she could digest and what would give her the most nutrients. Over time, the foods she was able to handle continued to increase in variety, and she was able to have the central line removed when she was a year-and-a-half old.

“Her intestines will continue to grow, absorption-wise, until she is 5 years old, but length-wise they will never grow back,” Sabrina said.

Savannah still has a gastrostomy tube, but it is only there as a safety measure and used for hydration when she is sick or needs additional fluids.

“The nice thing is, if we use it, she does not have to go to the hospital and have an IV,” Sabrina said. “We have tons of Pedialyte® in stock and we have a pump. Any day when we feel like she hasn’t had appropriate bowel movements, we run Pedialyte® all night long. It hydrates her for the next day and we go from there.”

Manuel and Sabrina keep Savannah on a very strict diet that they administer. The doctors say she can have whatever she wants like a normal kid, but as parents they have found what works and what doesn’t.

“We have learned that she is unhappy if she has whatever she wants. Some things make her tummy ache. Other times her bottom is red as can be, because if it doesn’t get absorbed, it comes out and it burns,” Sabrina said. “So she eats a lot of things that normal kids don’t eat. But she’s happy and she doesn’t have to have a central line.”

Savannah has been gaining weight and doing very well developmentally. Because of her short bowel syndrome, she needs to eat double the calories of a normal child her age every day in order to put on weight. She still has physical therapy ‑‑ because of her surgery. When she was a baby, she couldn’t have tummy time like other infants and she didn’t crawl or walk exactly on schedule, but otherwise she has been doing very well.

“The doctors are happy with her weight gain, but a little concerned about her length. We have to look at some medical options down the road, like growth hormones, to help her with her growth,” Sabrina said. “At this point, her thyroid numbers aren’t exactly where they should be, but as far as growth goes, she is going to grow until she is 14. We have plenty of time to keep watching and see if it is something that we have to intervene with.”

Geisinger caregivers, while keeping a close eye on Savannah, can definitely see that she is truly a miracle child.

“The reason that Savannah is alive is that her parents are very closely in tune to how she is, and when she was having trouble, they recognized it,” Dr. Coppola said. “The operations may have been at one single point in time, but it has been through the help of the gastroenterology team and the nutrition team, the bedside nurses and the ICU team ‑‑ everyone contributing to little baby steps forward from that major life-threatening illness to get back to where she is now: a little girl who is growing and going through all the usual development, laughter and fun that a kid her age should.”

Dr. Johnson agreed that it was the persistence of the family and their quick action that saved Savannah’s life.

“The thing about malrotation is you go from being well to being close to death in a short period of time. Any further delays here, could have impacted her,” she said. “If Sabrina would have waited until her scheduled appointment, if the ambulance would have broken down ‑‑ anything ‑‑ and this child would have died that night.”

Savannah sits in the family living room, snacking on popcorn, while listening to her parents talk about her. She enjoys singing the ABC song and “You Are My Sunshine.” She likes reading, or being read to, and loves Bubble Guppies, The Lion King and Paw Patrol.

“She loves doing chores,” Sabrina said. “She helps unload the dishwasher. She helps get the dog snacks.”

“She loves The Big Bang Theory. Oh my goodness, you would not believe it. She will sit there and say, ‘Big Bang’ and she will sit through and watch the entire episode,” Manuel said. “She will laugh at things that she shouldn’t be laughing at, like she gets it.

“As terrible as our situation was and has been, I always met someone at Geisinger that had it worse. I have always felt thankful, even in the midst of everything. My child is getting better ‑‑ even though it might take a while, she is getting better,” Manuel added.

For the Rodriguezes, it was their faith in God that provided them with the strength they needed along the way.

“We consistently pray for Savannah’s health and are very thankful to God for sparing her life and helping her along this journey,” Sabrina said. “God worked through Dr. Coppola, Dr. Johnson and all the caregivers at Geisinger to save her life.”

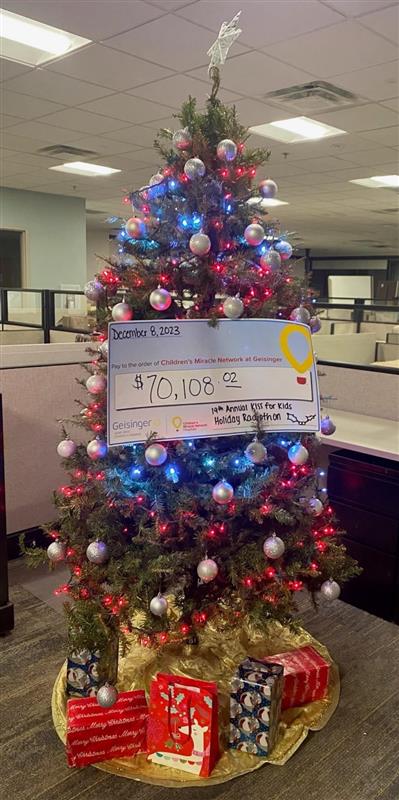

Donations to Children’s Miracle Network at Geisinger provided funds to provide life-saving equipment in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Geisinger Janet Weis Children’s Hospital. Items such as ventilators, bed warmers, monitors and more were used for her premature birth and after her life-saving surgery.